How health startups are turning blood testing and analysis into a sales funnel

Venture capital-backed startups layer slick interfaces on top of bloodwork from routine providers. But the real money isn’t in giving insights — it’s in what comes next.

Richard Adams thinks he might be “the most phlebotomized man in America.”

Adams, senior vice president of Quest Diagnostics' consumer unit, wears an Oura ring on his finger as well as a Whoop band on his wrist. He has helped strike deals with both brands, which are now part of a growing list of companies with lab analysis products powered by Quest.

“I’ve done them all,” Adams said.

As the wellness industry surges, a wave of startups are building sleek apps that reinterpret lab results, often using them as a funnel to sell treatments. Behind nearly all of them sits Quest, a decidedly non-startup company that has been publicly traded for nearly three decades. Quest quietly processes the samples while the startups build businesses on top of the data.

Adams said the company sees itself as an “ingredient brand” in the wellness boom. “We think that modestly, a venture-backed startup that is solely focused on user experience — they’re going to do great stuff and they’re probably going to do it a little bit faster than we are,” Adams said.

Investor attention is mounting. In the past year, Function Health and Superpower, prominent players focused on interpreting lab panels, have secured new funding rounds valuing the companies at $2.5 billion and $300 million, respectively. This momentum has drawn larger competitors, with wearables startups and telehealth heavyweight Hims & Hers launching similar lab analysis services in the last few months.

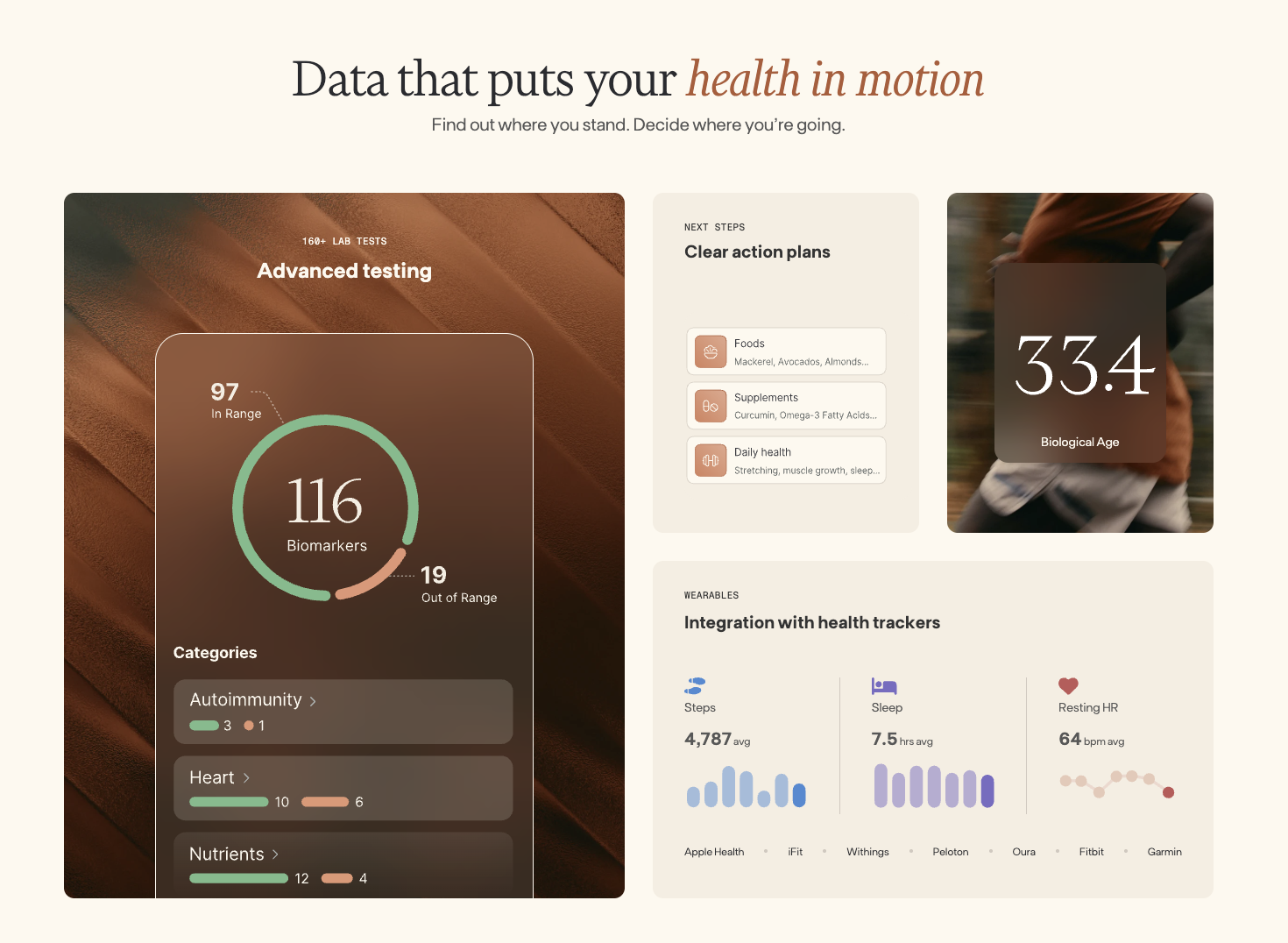

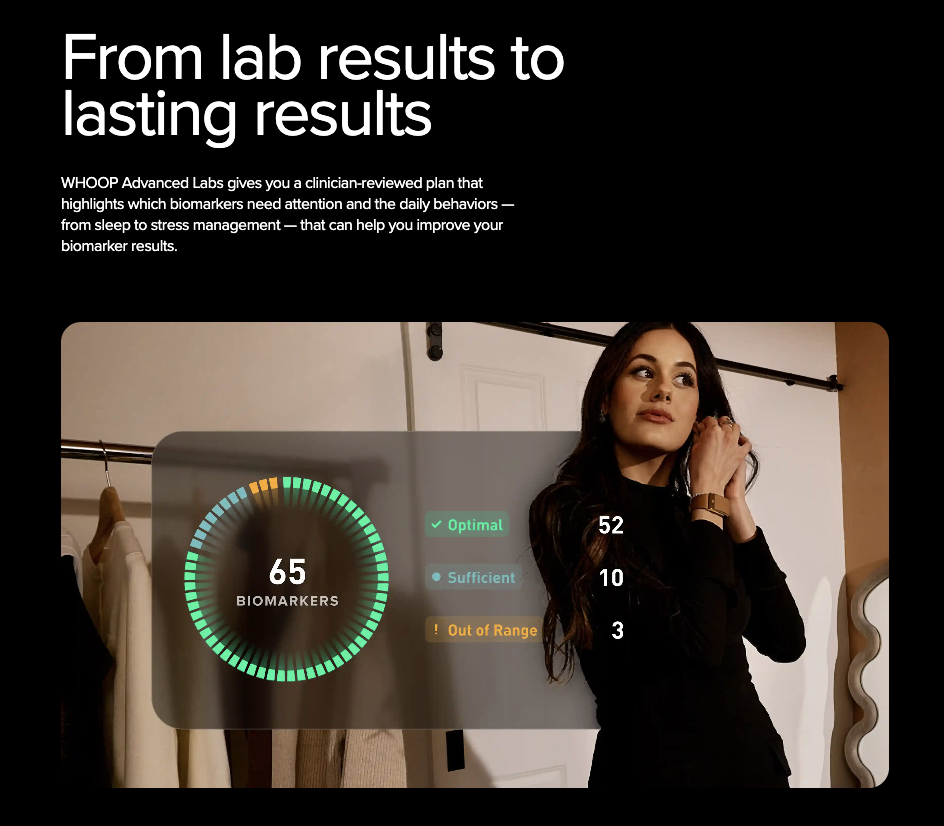

These startups sell memberships that come with lab tests — typically blood draws — that are done at Quest locations. Then an AI-powered, clinician-reviewed app analyzes the results and recommends action plans.

Startups like these largely cater to healthy people looking to get a granular look at their health and get ahead of chronic diseases. Considering many of them don’t have a diagnosis for a disease, treatment plans lean toward lifestyle changes or supplements.

While the words “startup” and “blood testing” may conjure images of Theranos, the fraudulent company founded by Elizabeth Holmes that promised to run dozens of tests from a single drop of blood, the testing here is real. It’s the interpretation and upselling that are new.

The lab biz

Quest and LabCorp make the majority of their money processing the routine blood tests and diagnostics ordered by physicians, hospitals, and insurers. Some of their more lucrative products are specialty panels, such as Alzheimer’s blood tests.

But consumer-driven testing, though still relatively small, has become a rapidly growing segment for the lab infrastructure giants. Quest’s own direct-to-consumer channel grew 30% to 40% on a year-to-date basis as of the third quarter of 2025, the company’s chief financial officer, Sam Samad, told analysts on October 21.

“Our partnerships with Whoop and Oura — we definitely expect that to contribute volume on the consumer health side,” Samad said.

It also has the potential to become higher-margin than its typical business because it does not face the hurdles the rest of its business does working through health insurance, Samad said at the Jefferies Healthcare Services Conference on September 29.

“There are no denials, there are no patient price concessions, bad debt that we have to chase from certain patients or unable to collect on if there’s co-pays or stuff in our usual business, which is the third-party payer business,” Samad said.

Labcorp has some partnerships with smaller names, like Marek Diagnostics and Frame, a reproductive and fertility startup. Labcorp CEO Adam Schechter told analysts on an October 28 earnings call that its consumer business has grown significantly but “it hasn’t reached critical mass at the moment for us to pull out the numbers and provide separate numbers.”

A spokesperson for Labcorp said its direct-to-consumer business now spans more than 100 tests, including 35 added in 2025, and said the company sees DTC testing “as part of a larger transformation in healthcare — one that emphasizes convenience, personalization, and proactive wellness and reflects the growing emphasis on functional medicine.”

Startups rely on Quest or Labcorp because of their national footprint. Even as the industry looks toward at-home blood collection as the next frontier, the technology remains difficult to execute. Current at-home kits are generally considered less accurate than in-clinic draws and detect a narrower range of biomarkers.

Hims acquired an at-home blood-testing facility, Trybe Labs, in February as part of a broader push to streamline its operations. This month it bought YourBio, which makes a device that uses “bladeless microneedles thinner than an eyelash” to collect blood painlessly. Hims did not respond to questions about why it still relies on Quest, rather than its own facilities, to process blood samples.

Companies are also pushing into deeper metabolic tracking. In September 2024, Abbott Laboratories released Lingo, a continuous glucose monitor linked to an app and subscription plan. Hims CEO Andrew Dudum teased a potential partnership in June, but one has yet to be announced. Oura has a partnership with Stelo, which makes a similar glucose-monitoring product.

Enter the startups

Ever since ChatGPT’s public launch in late 2022, users have been asking chatbots to interpret their bloodwork. Function — backed by Redpoint Ventures, A16z, as well as celebrities like Kevin Hart and Matt Damon — launched a beta version of its platform in April 2023.

The market has only gotten more crowded. Superpower, Function’s closest direct competitor, launched in April of this year. Wearable maker Whoop announced its lab offerings in September, and Oura did the same in October. Hims launched its Labs product in November.

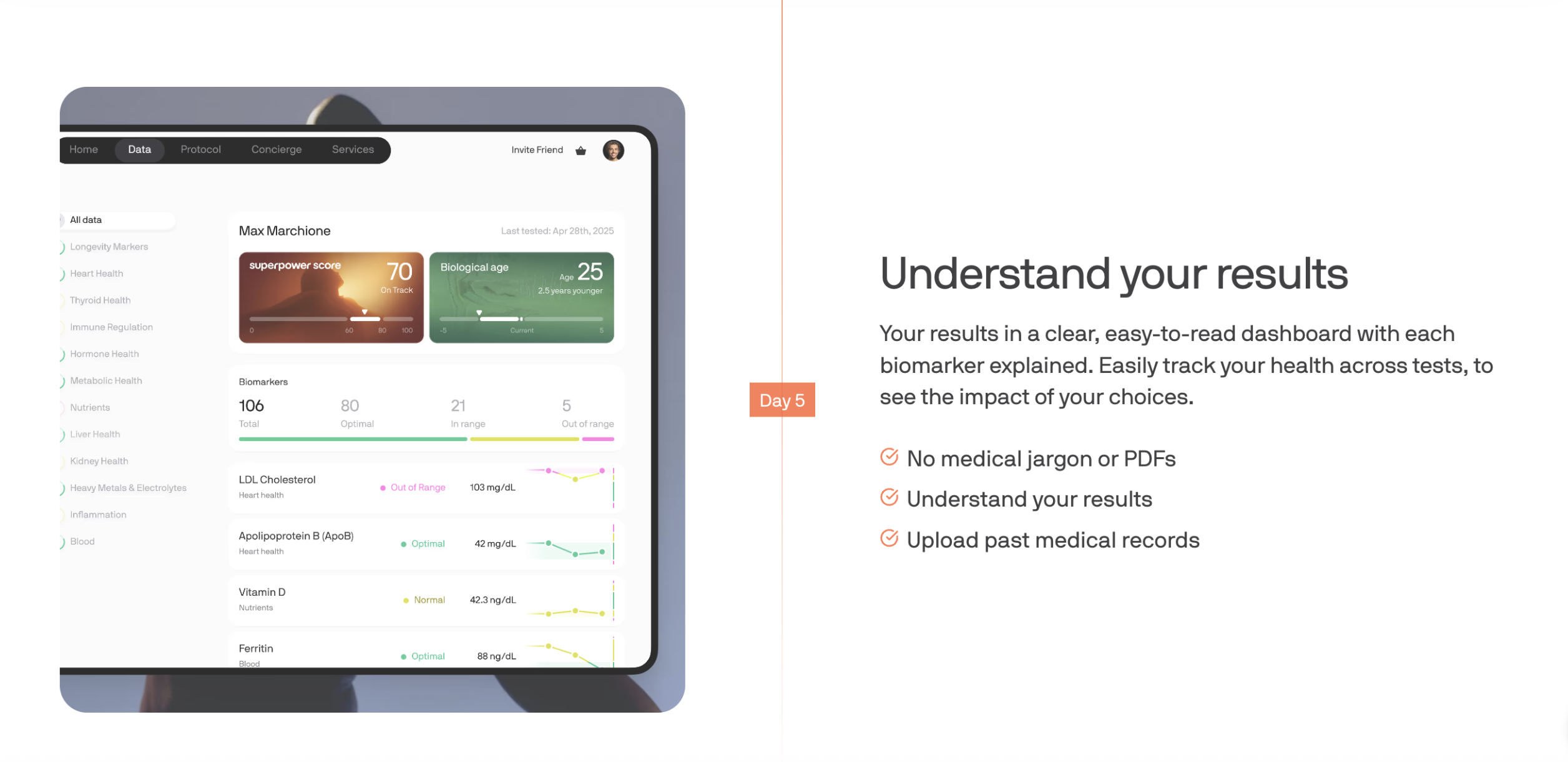

Each of these companies negotiates a price with Quest to fulfill a bespoke panel for their given platform. While the interfaces are slick, the business of reselling Quest’s lab tests isn’t particularly lucrative, Superpower cofounder Max Marchione said in an interview.

“My general view is that blood testing is a s--- business,” Marchione said. Diagnostics is “an incredible user experience, but that can’t be the business. The business has to be actually taking care of someone once they’re in the door, actually driving outcomes.”

Marchione criticized Hims’ decision to build its own lab infrastructure, arguing that it ties the business to a single diagnostic technology in a space where new testing methods are emerging quickly. He also argued that the real economics accrue to the major labs providers, not to companies selling biomarker interpretations. (Marchione told his employees, caveating that this wasn't financial advice, that he would go long Quest and short Labcorp, considering the latter has not focused as much on its DTC business.)

Superpower, for instance, has a supplement marketplace. Hims may recommend treatments like compounded GLP-1s, which it sells. Function recently told STAT it plans to launch a supplements offering “that is unlike anything that’s ever been in the marketplace before,” but did not go into detail.

Function declined to answer questions about its upcoming marketplace or where treatments and supplements fall in its long-term business model.

Dr. Ashwin Sharma, a medical strategy lead at HeliosX, a health tech company that owns brands like erectile dysfunction and hair-loss telehealth RocketRx, questioned whether companies like Function could make a profit off an annual subscription alone. He said telehealth companies like Hims are best poised to capitalize on consumer lab testing because they actually have a product to offer users.

“This is much more compelling and makes customers stickier,” Sharma wrote in his newsletter, GLP-1 Digest. “Even if results are ‘normal,’ there’s always something to up-sell or x-sell when you control the pharmacy.”

Sharma added that he “wouldn’t be surprised if we see acquisitions in this space over the next 12-18 months.”

“Gray area”

Some experts say the rise of expansive biomarker panels may have unintended consequences.

In an article published in The Lancet last year, researchers called direct-to-consumer medical testing “an industry built on fear,” preying on ostensibly healthy people’s anxieties that they may have serious health issues without experiencing any symptoms. In another journal, researchers said those tests “have a substantial risk of medicalization of healthy persons and damaging the trust in the reliability of healthcare laboratory testing.”

Once the lab results come back, these services present users with dashboards that flag anything out of range — using the same reference ranges they would see in a test ordered directly through Quest. Each company’s AI then generates recommendations it says were developed with input from doctors, ranging from lifestyle changes to products the company sells.

Blokes, a telehealth company focused on hormone treatments, added a lab analysis product that includes a 30- to 60-minute call with a doctor. “Data is only as good as the person interpreting it,” CEO Joshua Whalen said in an interview. “You can throw your labs in ChatGPT right now and get that. We think it’s just part of the equation.”

The use of bloodwork and health metrics to power AI features raises privacy concerns, as several companies allow themselves to use de-identified data for research, analytics, and product development.

The companies’ privacy policies show a significant variation in how they describe their obligations under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA. And while most claim compliance, this doesn’t necessarily mean the law applies to them in the first place, according to Suzanne Bernstein, counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center.

HIPAA generally protects health data collected by healthcare providers and insurance companies, but it does not cover data controlled by consumer-facing companies. This gap allowed genetic-testing company 23andMe, which tested users’ saliva in-house, to nearly auction off 15 million people’s genetic data when it went bankrupt earlier this year.

Labs like Quest or Labcorp are likely covered by HIPAA, but it’s unclear if patient data continues to be protected by HIPAA once it changes hands, Bernstein said. “It’s continuing to be a gray area, as consumer health products sometimes become primary healthcare for folks,” she said.