“Nowhere to go”: How tariffed companies weigh costly restructures vs. hunkering down and riding it out

We spoke to Columbia Business School professor and supply chain expert Nicole DeHoratius about how the tariffs will affect companies like Apple and what Intel can tell us about the reality of relocating operations.

The past few weeks have been a rollercoaster as global tariffs shift and change rapidly, making it hard to figure out what the trade wars actually mean for companies, for the US, for consumers, and even for innovation. We spoke with Columbia School professor and supply chain expert Nicole DeHoratius to try and get some grounding. Since we spoke Friday, a number of Apple products were exempted from reciprocal tariffs on China, but the administration has since clarified that the move is more procedural, and such goods would simply be moving to a semiconductor tariff basket, whose rates have yet to be announced.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sherwood News: I reached out to you April 7, when we were living in a completely different world. Then countries across the globe were facing steep US tariffs — 54% on Chinese imports — and our stock market was deep in the red. Now the stock market is still wobbly but the tariffs have been paused and mostly been diluted, except for China, where they’re currently at 145%, and China has responded in kind. What the hell is going on?

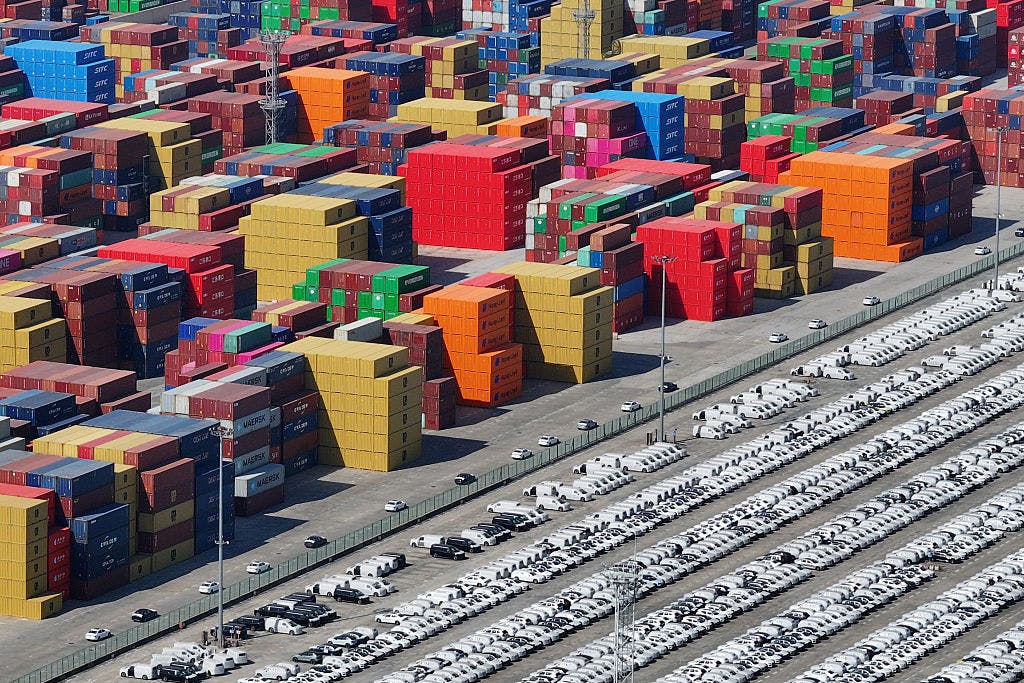

Nicole DeHoratius: I can’t speak to the pricing. The thing that I can speak to is really the chaos this creates for our supply chains, including tech and apparel. The apparel industry had been moving away from China for a combination of reasons — higher labor costs, inflexibility from the previous Trump term — and had been moving to Vietnam, to Bangladesh, to Cambodia, and now these are getting hammered as well. It just makes it really hard for them to readjust.

Broadly, it’s really difficult to understand how many links in the chain there are. And I’m surprised that after Covid we don’t recognize how incredibly interdependent our supply chains are. Things can’t move on a dime.

Sherwood: So these tariffs go into place — what happens?

DeHoratius: The desire to protect yourself from the tariffs means you’re going to move to some other location. But there seems to be nowhere to go at this point. Obviously it’s, yes, bring it back home. That’s the stated end goal. If that is the case, I’d like to see some other industrial policies in place for educating the workforce, getting people trained. State-of-the-art factories these days are automated, highly sophisticated computerized systems that we need to be able to run and operate, and we need people that can run and operate them.

Sherwood: How feasible is it that the US can run and operate them as is?

DeHoratius: We need only look at Intel’s delayed factories in Ohio. Shortly after they were announced were all these warnings: we don’t have enough folks to run the factories. How are we going to train these people?

Keeping that in mind, if we want to bring things back home, we need to be also working on multiple dimensions to make that happen, not just tariffs.

Sherwood: What about the iPhone? The administration won’t stop talking about building it in the US. My understanding is that while Apple may be able to move final assembly and testing to the US, it would still have to ship semi-assembled parts from places like China, and even that would drive up costs a ton. Will the latest tariffs actually force tech companies to bring manufacturing to the US?

DeHoratius: I think people are looking. They want to have a diversified supply chain. That was pretty clear after Covid. The question is, “What makes sense?”

What I tell my students is that you’re going to locate your manufacturing sites where there’s access to raw material. If we think about those phones, what are some of the raw materials? The second thing that I ask my students is, “Where is the market growing?” Is our consumer market growing in the US as fast as it’s moving in Asia or India, et cetera?

The answer is that all evidence shows that the future of markets is really in Asia. If we want to be serving those markets, we need to be located near those markets.

We’re thinking about moving to the US to serve the US market, but these are global companies and the fastest-growing market for some of these is not necessarily in the US. It’s not just, let’s optimize for the American supply chain, but where are our future customers? And how do I make sure that I’m building a supply chain for the future?

Sherwood: But is the US market big enough that they’re going to have to at least manufacture here the stuff they sell here? Or do they just deal with these tariffs and lower margins and higher prices?

DeHoratius: That’s the thing: they can do it but at what price? At what price are they going to then have to sell the goods in order to make a profit on that? And then obviously if you increase the price, that influences demand, and here we are again.

Sherwood: So to the extent it does happen, at what scale? Do some companies move some of their factories? What ends up actually happening?

DeHoratius: I don’t have a crystal ball, but if I were thinking about this problem, I would be wondering, “How long is this going to last?”

Is this going to last beyond one administration? In which case, do I need to think about restructuring? Or can I hunker down for a bit until it disappears, if it will disappear? But the timeline for many of these factories is well beyond one administration.

It’s one thing to just hold the finished goods inventory here in the US and then distribute it. It’s a whole other thing to build a factory from scratch. The Intel example might be a good one. They started in 2022. How far along are they, how long are they taking to build it, and what have they been saying about the lack of manpower along the way?

Sherwood: It looks like now the first factory is slated to open in 2030. So, quite a while from start to even the beginning of the finish.

DeHoratius: For high-tech stuff, it takes quite a while. You’ve got to get the machinery in — and now there will be tariffs on that — get the permitting for the water usage, get the builds in. All that kind of stuff is going to take time.

Sherwood: We have these giant global companies with global markets. They’re watching these tariffs ricochet around and go away and come back. There definitely seems like there will be a big tariff on Chinese goods, at least, where a lot of tech stuff is made. Pretend you’re the CEO of one of these big US tech companies: do you pause? Put your head in the sand? What do you do?

DeHoratius: I would be running simulations to see what’s feasible. Let’s say I have a portfolio of products, each of which has raw materials from different locations. So this is a huge, complex problem and I’m running simulations on what can I move where. What other countries have the capability to do this quickly, maybe as a stopgap approach while I build in the US? That’s a potential option. So I’m doing a bunch of scenario planning to figure out what are a few key alternatives, conditional, of course, on things staying the same.

Sherwood: That appears to be what Apple is doing. It’s ramping up production in India. It’s pivoting iPhones it makes in India to be sold in the US rather than as many Chinese ones. It’s shipping cargo jets with hundreds of tons of iPhones to the US to beat the tariffs. It feels like Apple’s not so much following the intent of the tariffs — to build in the US — as it is hacking it.

DeHoratius: I mean, you’re optimizing. You’re doing what’s best.

Sherwood: What do you think is the most likely effect of all this on the US consumer? We stop getting certain stuff? Stuff gets more expensive? Stuff gets different? We stop buying from Amazon as much?

DeHoratius: I think everybody will feel the higher prices once they start to embed those, if they haven’t already, into the pricing mechanisms. The other day I was listening to somebody say, ‘Well this is great for the environment because it just means Americans are going to stop buying more.’ Well, that’s coming from the perspective that you have surplus to buy a lot more. There are some people that just don’t have that surplus and are buying because they need it today. So I think it’s really going to be mixed. There are going to be people for whom this is really harmful. For others, they might change their buying behavior and maybe buy less. There are going to be differences depending on the demographics, and some people will be able to wait it out longer than others.

The lower-income demographic does not have the buffer to absorb a lot of these prices, so it becomes even more difficult and challenging for them, and they were already in a hard place to begin with.

Sherwood: Let’s talk about Tesla. Tesla just stopped taking orders for its US-made cars in China, but that was a really small portion of what it sold there anyway. Tesla has big factories in China that produce cars for China and Europe, so it wouldn’t have to face US tariffs there. For Teslas sold in the US, they’re made in factories in the US, but obviously the company is on the hook for parts it imports from Canada and Mexico.

But overall, is Tesla safer because to some extent it manufactures in the places it sells?

DeHoratius: It builds incredibly robotic factories, so it also depends on where those robotics are made. Tariffs could also cause the buying power for the American consumer to go down, so demand for cars and Tesla could go down. But to answer your broader question, if I’m serving the market where I have manufacturing locations, you can avoid many of those and you would imagine that you would be better off because not all of your items are going to have tariffs on them. That’s going to be true for all different types of car manufacturers, not just Tesla.

Sherwood: I’ve been hearing about the end of globalization, but that was at the beginning of the week when there were huge tariffs across the world. What do you think now?

DeHoratius: I think supply chains rely a lot on trust. And I think we have put trust that takes a long time to build at risk. That’s the thing that worries me the most. Globalization depends on that. There’s a trust within our supply chains and trust is hard to build. You have to have a partnership and a belief that when I place that order, you’re going to deliver a high-quality item on time, in full, with the parameters that I’ve specified. To now shift to unknown parties — you’ve got these third-party logistics companies, other networks that you’re going to have to build — that will take some time to build trust within those networks.

Sherwood: I was thinking about that with Apple moving production to India. How long will it take for those supply chains to get up to speed with what they had in China, where they’ve been doing this forever?

DeHoratius: There are learning curves and there are going be yield effects. You might get a really good yield from the factory that you’ve trained for the last 10 years because you’ve been auditing it and you’ve been monitoring it, and the workers get better over time. All of this will need to be readjusted.

Even mundane things like when I tell you that I want a six-foot pallet because that six-foot pallet will fit into my shelving units. One entity is measuring the six feet from the top of the pallet, the other is measuring it from the floor to the top of the pallet. Then you’ve got this discrepancy and they ship and the whole shipment doesn’t fit into the shelving units. Those are seemingly minor, but you add them up across multiple shipments over multiple weeks and across a bunch of new suppliers, and you’re going to have glitches that impact performance.

Sherwood: Finally, more broadly, technological innovation in the US has been deeply integrated with globalization. A big tech company is very dependent on getting raw materials and chips and specialized labor from around the globe. How might these tariffs and their knock-on effects ultimately affect technological innovation?

DeHoratius: Am I going to make any big moves and big investments right now? Probably not. There’s a professor at Berkeley, Lee Fleming, who does a lot of work on innovation. They talk a lot about the global flow of ideas and how that contributes to innovation. And any time that is halted or stopped, that’s a problem for generating new ideas and potentially innovation.

From the product design side, you’ve got a lot of the designers here. But design goes hand in hand with manufacturing. If you’re breaking those connections where you’re designing for manufacturing, and the manufacturer is giving you new techniques and new ideas, that could be problematic. The flip side is also true. You could be building new connections with suppliers that you never had links with before. But again, that will take some time to foster because you have to have trust to be able to share those ideas.

So if I’m a supplier to Apple, I don’t want to give them my idea and for them to go run with it on their own. I have to have the trust that we’re going to do this together.